Happy Thanksgiving

Here’s Inugami, Yokai No60 in the collection and last minor Yokai.

I will now take a little break to attend to some commissions and other personal projects.

Will be back on those Yokai probably beginning of January.

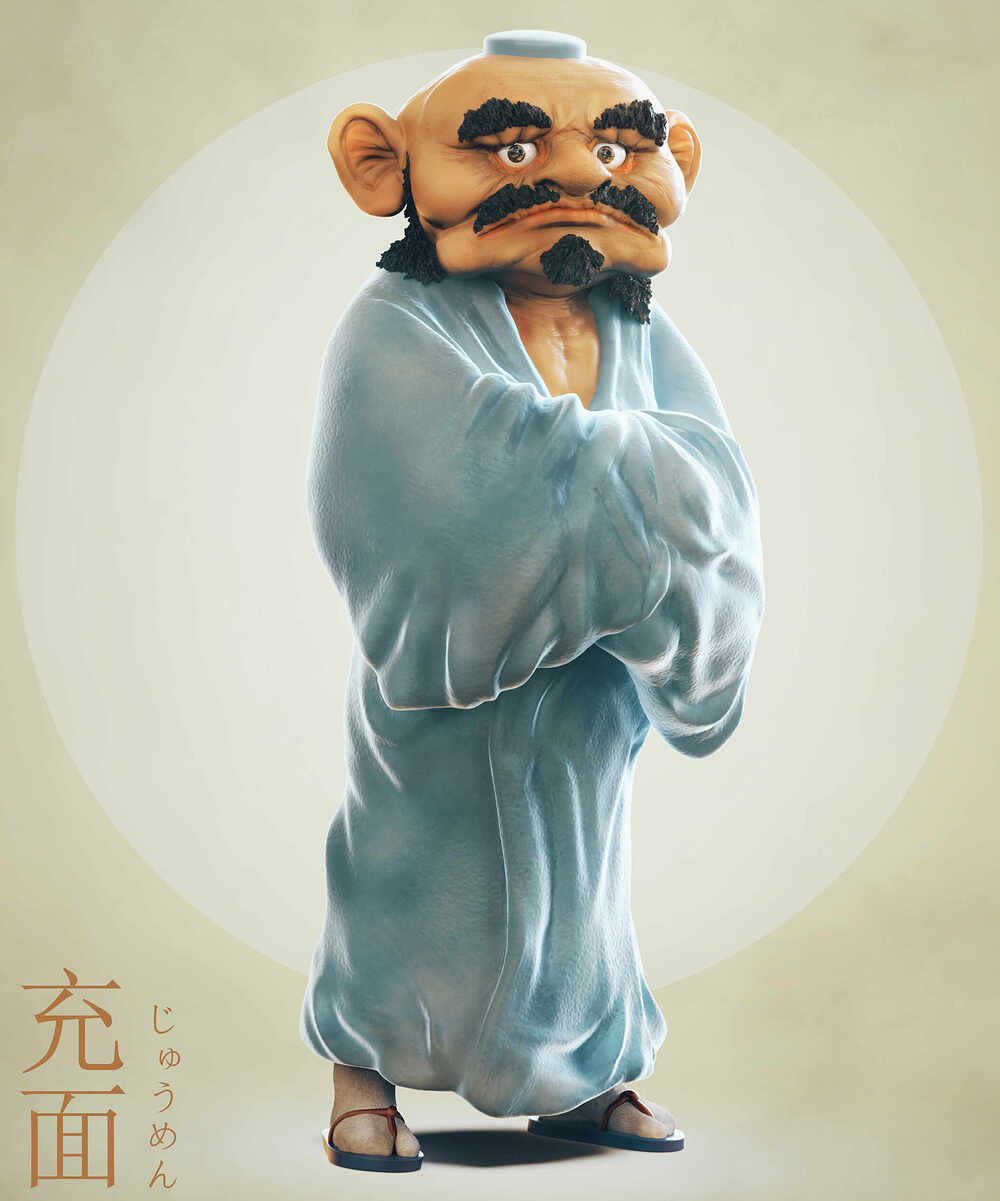

Inugami

犬神

いぬがみ

Translation: dog god, dog spirit

Alternate names: in’game, irigami

Habitat: towns and cities; usually in the service of wealthy families

Diet: carnivorous, though they are usually starved on purpose

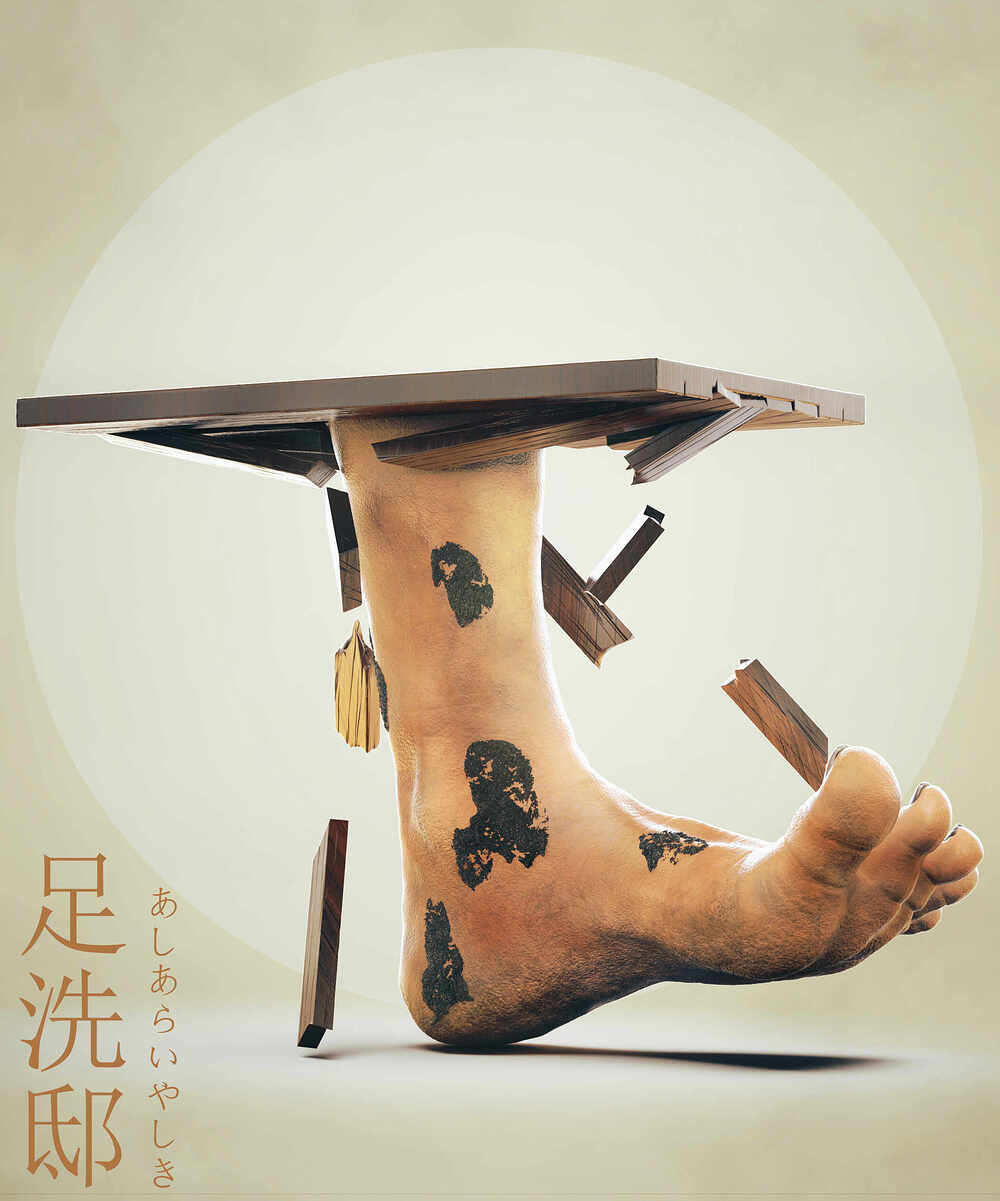

Appearance: Inugami are a kind of familiar, or spirit of possession, which are found in Kyushu, Shikoku, and elsewhere in West Japan. In public, an inugami looks identical to an ordinary dog in order to blend in with society. However, its true form is that of a desiccated, mummified dog’s head, often dressed up in ceremonial trappings. This is kept safe (and away from prying eyes) in a secret shrine in its owner’s house.

Behavior: Inugami have much in common with other familiars, such as shikigami and kitsune-tsuki. Inugami are more commonly used in areas where foxes are not found, such as major population centers. There is even evidence of an ancient tradition of Inugami worship stretching from Western Japan down to Okinawa. Powerful sorcerers were said to be able to create these spirits through monstrous ceremonies and use them to all sorts of nefarious deeds. Inugami serve their masters loyally, performing tasks just like a faithful dog. They are loyal to one person or one family only, and unless seriously mistreated they remain loyal forever; these spirits can be passed down from generation to generation like an heirloom.

The technique for creating these fetishes was passed down along bloodlines, and such families are known as inugami-mochi. These families would keep their inugami hidden in the back rooms of their houses, under their beds, in dressers, or hidden among water jars. It is said that a family owned as many inugami as there were members of the household, and when a new person joined the family, they too received their own familiar. Inugami were treated like family members by inugami-mochi families, and most of the time would quickly run out to do their master’s bidding any time their master wanted something. However, like living dogs, occasionally a resentful inugami might betray a master that grew too abusive or domineering, savagely biting him to death. And while inugami, like other familiar spirits, were created to bring wealth and prosperity to their families, occasionally they might also cause a family to fall into ruin.

Interactions: Like other tsukimono, or possession spirits, inugami are beings of powerful emotion and are very good at possessing emotionally unstable or weak people. They do so usually by entering through the ears and settling into the internal organs. People who have found themselves possessed by an inugami — or even if it was only suspected that a person might be possessed — were in for some serious misfortune. The only way to be cured of inugami-tsuki is to hire another sorcerer to remove it. This could take a very, very long time and involve a lot of money. Signs of inugami possession include chest pain, pain in the hands, feet, or shoulders, feelings of deep jealousy, and suddenly barking like a dog. Some victims develop intense hunger and turn into gluttons, and it is said that people who die while possessed by an inugami are found with markings all over their body resembling the teeth and claw marks of a dog. Not only humans, but animals like cows and horses, or even inanimate objects, can be possessed by inugami. Tools possessed by such a spirit become totally and completely unusable.

Practicing this sort of black magic was illegal and strongly frowned upon, although that didn’t stop the aristocracy from dabbling in sorcery, known as onmyōdō. If an inugami-mochi family was even suspected of cursing another family, the accused person would be forced to apologize and leave his comfortable estate to live on the outskirts of town, secluded from family, friends, and the comfortable aristocratic life. Even if the alleged victim was eventually cured of his possession, the accused (and all of his offspring for all generations to follow) usually had to maintain a solitary lifestyle, outcast from the rest of society, to be viewed by others as wicked and tainted.

Origin: How long the practice of creating inugami begun is unknown. However, by the Heian period (some 1000 years ago, at the height of classical Japanese civilization) the practice had already been outlawed along with the use of other animal spirits as tools of sorcery. According to legend, the creation of an inugami is accomplished like this: the head of a starved dog must be cut off (often this was accomplished by chaining a dog up just out of reach of some food, or else burying it up to its neck, so that it would go berserk out of desperate hunger and its head could be cut off at the point of greatest desperation). Then, the severed head is buried in the street — usually a crossroads where many people pass. The trampling of hundreds or thousands of people over this buried head would add to its stress and cause the animal’s spirit to transform into an onryō (a powerful maleficent spirit). Occasionally these severed heads were said to escape and fly about, chasing after food, animated solely by the onryō’s anger — such was the power of the dog’s hunger. The head was then baked or dried and enshrined in a bowl, after which the spirit could be used as a kind of fetish by a wicked sorcerer, doing whatever he or she commanded for the rest of time.